The NIS2 Directive (Network and Information Security 2) is a new legal act that replaces the earlier NIS1 Directive of 2016. The Directive entered into force on 16 January 2023, and Member States were required to transpose it into their national legal systems by 17 October 2024. Poland, like France, Spain, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Bulgaria, has not yet completed this process. However, the national legislative process is currently at an advanced stage.

Objective of the Directive

The primary objective of the Directive is to strengthen protection against digital threats across the European Union. It introduces uniform cybersecurity rules for sectors that are critical to the economy and society, including energy, transport, healthcare, digital infrastructure, banking, and the maritime economy. The regulation obliges Member States to develop national cybersecurity strategies, enhances cross-border cooperation in responding to major incidents, and grants supervisory authorities stronger powers to monitor compliance and enforce the provisions.

What does the implementation of the NIS2 Directive look like in Poland?

In Poland, the NIS2 Directive is being implemented through an amendment to the Act on the National Cybersecurity System. To date, the legislative work has involved two draft bills. However, it was only the second draft that softened the most heavily criticised solutions, including, among others:

- the mandatory application of ISO standards, which was ultimately abandoned,

- the deadlines for conducting the first audit, which were extended,

- supply chain requirements, which were limited to direct suppliers.

The draft amendment adopted by the government:

- expands the catalogue of entities subject to the obligations,

- introduces new incident response teams (sectoral CSIRTs),

- strengthens the powers of supervisory authorities, such as the Minister for Digital Affairs and CSIRT GOV.

Entities covered by the new regulations will be required, inter alia, to conduct risk assessments, implement security measures, train employees, and report incidents. It is anticipated that the new provisions will enter into force around mid-2026.

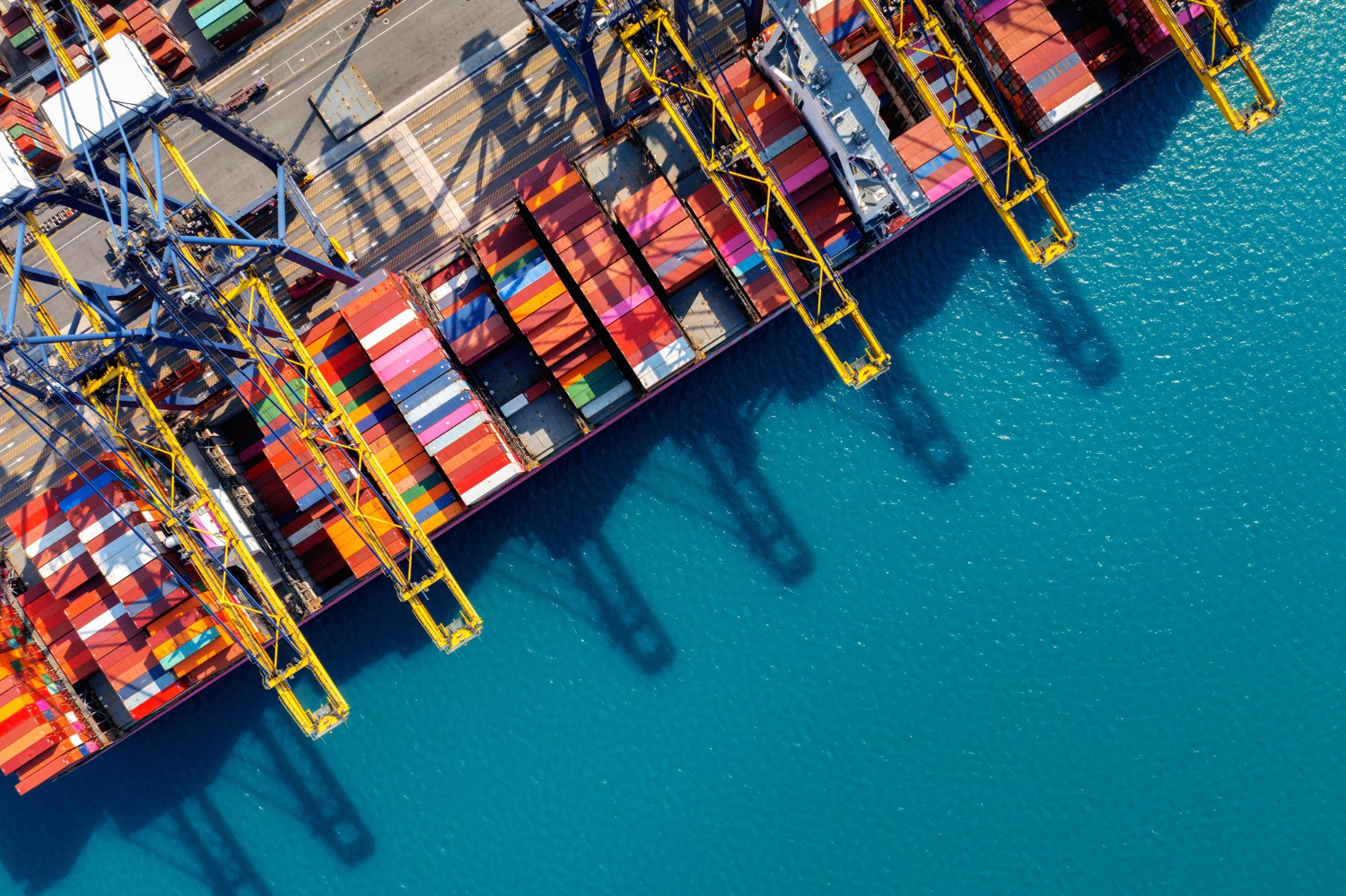

The maritime sector – who is covered

Importantly for businesses, the NIS2 regulations introduce a differentiated supervisory model. Under this model, certain organisations will be subject to particularly intensive supervisory obligations. This applies to so-called essential entities, for which the legislator has envisaged more far-reaching oversight than for other participants in the system. The transport sector, including maritime transport, is classified as an essential sector due to its significant role in the economy and society.

In practice, the NIS2 regulations primarily affect entities operating on a larger scale, which ensure the continuity of transport and logistics processes. These are mainly organisations that employ at least several dozen employees and generate substantial annual revenues.

In the maritime sector, this primarily concerns:

- operators of maritime, inland waterway, and coastal transport (both passenger and cargo),

- port authorities,

- entities carrying out work and operating equipment within ports,

- operators of vessel traffic systems.

Such entities will be required to implement the full set of NIS2 requirements. It should also be emphasised that the size criterion is relevant, although it is not always decisive. In certain cases, inclusion under the regulations depends on the importance of a given activity for the functioning of the state or for ensuring the continuity of services.

This approach ensures that protection covers the entire critical maritime infrastructure, which is vulnerable to cyberattacks capable of paralysing trade and logistics.

Obligations for maritime entities and the significance of NIS2

- Entities operating in the maritime sector will be required to:

- regularly assess cybersecurity risks to IT and OT systems (operational technology, e.g. port control systems),

- implement incident response procedures and report serious breaches,

- train personnel on digital threats,

- ensure supply chain security (although, in the Polish draft, this has been limited to direct suppliers),

- cooperate with other entities and authorities in the exchange of information on threats.

A key novelty is the explicit emphasis on the responsibility of senior management for overseeing the implementation of cybersecurity obligations. This means that cybersecurity issues cease to be the exclusive domain of IT departments and become an element of managerial accountability.

The implementation of NIS2 is undoubtedly a challenge in terms of costs, as it involves investments in technology, audits, and training. However, it also delivers numerous benefits by strengthening resilience to incidents, which in the long term will help minimise financial losses and the risk of losing critical data. It also enhances international cooperation and improves the exchange of information on threats.

From a reputational perspective, the regulations may also affect competitiveness and development opportunities. Companies that meet high cybersecurity standards gain the trust of global partners, while the modernisation of IT/OT systems can deliver operational efficiencies (e.g. in offshore wind projects or logistics).

The significance of the ISPS Code

The International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPS) Code was developed in response to global security threats that emerged at the beginning of the 21st century and led to strengthened protection of port and maritime infrastructure. ISPS regulations focus primarily on a systemic approach to the security of ports and vessels, encompassing threat assessments, the organisation of protective procedures, and the preparation of personnel to respond to incidents. The NIS2 Directive extends this approach into the area of cybersecurity, placing emphasis on the resilience of information and technological systems to increasingly sophisticated digital threats.

Integrating NIS2 requirements with existing ISPS mechanisms enables ports and maritime operators to build a coherent security management system in which physical and digital risks are analysed jointly and incident response is coordinated.

For Polish ports, this represents an opportunity to modernise security systems. Combining the new procedures introduced by the Directive with existing security plans based on the ISPS Code will help avoid duplication of efforts and create a single, coherent risk management framework covering both digital and physical security.

Current situation in the maritime sector

As of December 2025, the Polish national legislation implementing NIS2 has not yet entered into force, and the legislative process is in its final stage. This means that entities operating in the maritime sector are not yet subject to formal obligations arising from the new act.

However, many port operators and shipowners are already voluntarily preparing for implementation. This includes modernising IT infrastructure, integrating NIS2 procedures with existing ISPS security plans, and investing in training.

The maritime sector is facing significant changes, but the full set of obligations will only apply once the amendment to the Act on the National Cybersecurity System is adopted and enters into force—most likely in the first half of 2026.

The NIS2 Directive represents an important step towards strengthening cybersecurity across the European Union. For seaports and maritime sector entities, it entails not only new regulatory obligations, but above all an opportunity to enhance operational resilience and competitiveness.